At the end of November 2005 I showed the ‘Crystals and Curves’ programme in the Avanto Festival in Helsinki. It was originally put together as part of a much larger manifestation which took place in 2004 at the Dutch Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. This programme was called ‘4D in the Filmmuseum’ and it focused on the fascination of artists with images and concepts from science and technology.

László Moholy-Nagy: Lichtspiel Schwarz-Weiss-Grau

(16mm, 1930, 5’30, b/w, silent 24fps)

This is the film László Moholy-Nagy made of his ‘Licht-Raum-Modulator’, one of the first kinetic sculptures and probably his best known work. An important part of the sculpture is not the material object itself, but the play of light and shadow in the space around it: these shadows show the elements of the sculpture in ever changing constellations and thus show a glimpse of a ‘fourth dimension’. This film is a composition of the light and shadow patterns generated by the Licht-Raum-Modulator, and originally Moholy-Nagy thought this to be the sixth and final part of a much longer film, dealing with space-time.

Henri Chomette: Jeux de reflets et de vitesse

Henri Chomette: Jeux de reflets et de vitesse

(16mm, 1923-25, 6′, b/w, silent, 18fps)

Henri Chomette was the brother of René Clair and made two experimental films, both originally as part of a collaborative project with Man Ray. “The cinema is not limited to the representative mode. It can create, and has already created a sort of rhythm…Thanks to this rhythm the cinema can draw fresh strength from itself which, forgoing the logic of facts and the reality of objects, may beget a series of unknown visions, inconceivable outside the union of lens and film. Intrinsic cinema, or if you prefer, pure cinema – because it is separated from every other element, whether dramatic or documentary, is what certain works lead us to anticipate…” (Henri Chomette, 1924)

J.C. Mol: Uit het rijk der kristallen

J.C. Mol: Uit het rijk der kristallen

(35mm, 19??, 13′, b/w, sound 24fps)

The title of this film translates as ‘From the Realm of the Crystals’, and it shows the enormous variety of crystal shapes under the microscope. J.C. Mol is the father of Dutch scientific cinematography, and this film was as famous amongst scientists as it was amongst the Dutch avant-garde filmmakers of that time, such as Joris Ivens. It was admired because of its photographic beauty and often discussed together with the early abstract films of the twenties and thirties.

Hy Hirsch: Gyromorphosis

(16mm, 1956, 7′, colour, sound, 24fps)

The subject of this film is a sculpture by the Dutch painter and sculptor Constant Nieuwenhuis. Many of his sculptures are related to his ‘New Babylon’ project and are sketches of an utopic city of the future, in which all ‘homo ludens’ are nomads and do nothing but play: “They wander through the sectors of New Babylon seeking new experiences, as yet unknown ambiances. Without the passivity of tourists, but fully aware of the power they have to act upon the world, to transform it, recreate it. They dispose of a whole arsenal of technical implements for doing this, thanks to which they can make the desired changes without delay. Just like the painter, who with a mere handful of colors creates an infinite variety of forms, contrasts and styles, the New Babylonians can endlessly vary their environment, renew and vary it by using their technical implements.” (Constant Nieuwenhuis, 1974)

Jun’ichi Okuyama: Shinto-Ga, Osmography

(16mm, 1994, 9′, b/w, sound 24fps)

A cameraless film which was made by making contact prints of objects directly on the film strip. The image track is also identical to the sound track: the images you see generate the sounds you hear.

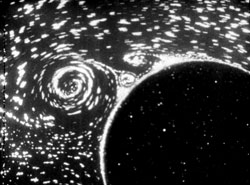

O. Tietjens, L. Prandh: Entstehung von Wirbeln bei in Wasser bewegte Körpern

O.Tietjens, L.Prandh: Entstehung von Wirbeln bei in Wasser bewegte Körpern

(35mm, 1925, ca. 10′, b/w, silent 18fps)

One of the strictly scientific films in this programme, this film was made at the university of Göttingen, in Germany, and was part of the collection of the Dutch State Aerospace Research Service. It shows a sequence of experiments dealing with the movements in fluids and has gorgeous images of turbulences and vortexes.

Stan Brakhage: Commingled Containers

(16mm, 1996, 4′, colour, silent 24fps)

This film can be considered as the filmic testament of Stan Brakhage. He made it towards the end of his life as he was preparing for cancer surgery. It is the culmination of his interest in ‘refracted light’, which started with his famous film The Text of Light from 1974. Brakhage said the title refers to bubbles, water, and life itself as commingled containers.

Len Lye: Particles in Space

(16mm, 1979, 4′, b/w, sound 24fps)

Particles in Space is one of the last films Len Lye was able to finish, and it is one of the films he made by scratching onto black film. The film represents a kind of ‘automatic writing’ by Len Lye: repeating the same gestures over and over with tiny variations to achieve an incredible control over the movements in the film.

Larry Cuba: 3/78

Larry Cuba: 3/78

(16mm, 1978, 6′, b/w, sound)

Larry Cuba taught himself computer animation at the Jet Propulsion Lab before becoming the assistant of John Witney for his film Arabesque. Cuba himself made four films in the course of his thirty year career, which can be seen in the balanced contruction of his films and his attention to detail. In this film, 16 objects, each consisting of 100 luminous points, go through a series of precisely choreographed rhythmic transformations.

Robert Fairthorne, Brian Salt: Equation X+X=0

(35mm, 1936, 5′, b/w, silent)

Animationsof lines in motion were seen as an useful way to visualize mathematical concepts or mathematical proofs. Most mathematical films have been made as an aid for teachers, and this film is no exception. Robert Fairthorne was a mathematician with an immense interest in avant-garde film, and he saw aesthetic potential in the educational animations Brian Salt was making. ‘If abstract films are really abstract films …they deal exclusively with those abstract relations that can be expressed in terms of shape and motion’, wrote Robert Fairthorne in 1936.

Stan Vanderbeek: Symmetricks

(16mm, 1971, 6′, b/w, sound)

An early computer animation, descibed by Vanderbeek as ‘digital fingerpainting’. Curves drawn on the computer screen by way of a light pen are then mirrored and multiplied.

Thierry Vincens: Giraglia

(35mm scope, 1968, 6′, colour, sound)

This film is the perfect counterpoint to its famous soundtrack: the music Pierre Henry and Michel Colombier had made the year before for the ballet Messe pour le temps présent by Maurice Béjart. It is one of the most spectacular abstract films ever made: in gorgous colourful cinemascope, the screen explodes again and again with textures of hot wax in cold water.